How the French and English shaped Canada: The rise and fall of New France

Publié le 18/05/2025

Extrait du document

«

How the French and English shaped Canada: The rise and fall of New

France

Sencanada magazine, October 16, 2018

The fleur-de-lis and the Tudor rose, the salamander and the lion: symbols of

English and French rule are everywhere in Parliament Hill’s Centre Block.

Portraits of the French monarchs who governed New France from the 16th century

to the 18th century hang in the Salon de la Francophonie.

Nearby, in the Senate

foyer, are the British monarchs who succeeded them.

It’s a celebration of Canada’s colourful and sometimes turbulent history of French

and English coexistence.

A bronze portrait of King Henri IV hangs in the Salon de la

Francophonie.

He rebuilt a French economy battered by 36

years of religious civil war and personally financed several of

explorer Samuel de Champlain’s expeditions.

Samuel de Champlain explored Canada’s East

Coast, Great Lakes and St.

Lawrence River,

including its tributaries, between 1603 and his

death in 1635.

He established the first

permanent colonies in Canada and opened up

France’s fur trade with local Indigenous

trappers.

.

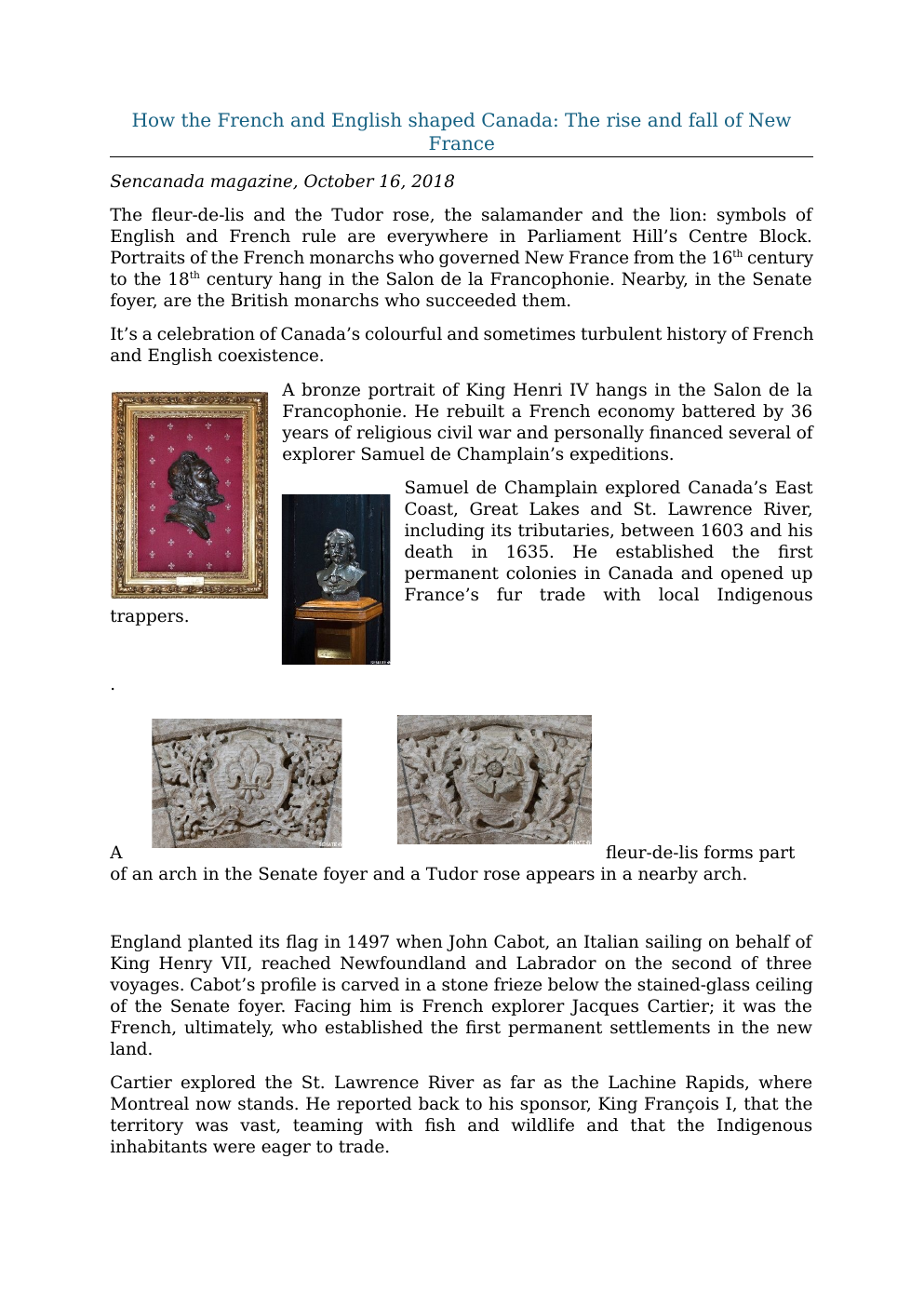

A

fleur-de-lis forms part

of an arch in the Senate foyer and a Tudor rose appears in a nearby arch.

England planted its flag in 1497 when John Cabot, an Italian sailing on behalf of

King Henry VII, reached Newfoundland and Labrador on the second of three

voyages.

Cabot’s profile is carved in a stone frieze below the stained-glass ceiling

of the Senate foyer.

Facing him is French explorer Jacques Cartier; it was the

French, ultimately, who established the first permanent settlements in the new

land.

Cartier explored the St.

Lawrence River as far as the Lachine Rapids, where

Montreal now stands.

He reported back to his sponsor, King François I, that the

territory was vast, teaming with fish and wildlife and that the Indigenous

inhabitants were eager to trade.

It was King Henri IV, whose portrait hangs near François I’s in the Salon de la

Francophonie, who seized this commercial opportunity.

He enlisted Samuel de

Champlain, a man often referred to as the “Father of New France”, to open up

trade in the New World.

Champlain, whose bronze bust stands nearby, led dozens

of expeditions in the 1600s, establishing permanent settlements at Port Royal on

the Bay of Fundy and at Quebec City.

King Louis XIV made populating the territory a priority and, by the 1700s, it

seemed like New France was about to bloom.

However, an awkward alliance with

Austria, Russia and Spain dragged France into the Seven Years War in 1756.

Known in North America as the French and Indian War, it was a sprawling conflict

that ended up benefiting Great Britain at everyone else’s expense.

Two centuries of French rule began to unravel in the 1750s.

King Louis XV is the

last of nine Ancien Régime kings whose portraits hang in the Salon de la

Francophonie.

These French monarchs governed New France from the 1500s to

the 1700s.

King George III, whose portrait hangs around the corner in the Senate foyer, is

the first of nine British monarchs who succeeded them.

French and English heraldic symbols,

including the fleur-de-lis, the Tudor

rose and the Tudor Crown, embellish

a clock in front of the Senate

Chamber’s public gallery.

A Tudor rose,

a traditional emblem of England, is

carved in the back of the Senate

Speaker’s chair

France, heavily committed to fighting in Europe, stretched what few resources it

had to defend its scattered colonial outposts.

Britain’s increasingly powerful navy

harassed it on all fronts.

The Fortress of Louisbourg....

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- What are the influences of the Gilead society and how they have an impact on the woman’s lives?

- Isaac Newton I INTRODUCTION Isaac Newton (1642-1727), English physicist, mathematician, and natural philosopher, considered one of the most important scientists of all time.

- Essay English : In Arthur Miller's play "All my sons", Joe Keller is a hero in his family and in the neighborhood even if he did some very awful things.

- Placed under the dual sovereignty of the bishop of Urgel and thePresident of the French Republic, Andorra is the highest inhabitedcountry in Europe.

- The Rights of Man DeclarationWith this declaration, the French National Assembly addressed many of the French people's grievances with the monarchy and established the ideals of the FrenchRevolution.